This past spring, after more than eight months of debate, the Virginia Board of Education approved new education standards. They outline how educators within the state should teach history and social studies. This applies to students from kindergarten to 12th grade.

The board presented a first draft of the proposed history curriculum last August. Under normal circumstances, the board would have accepted the draft for review and a mundane judicial process would have followed. But this time, it drew extreme amounts of attention and led to four different drafts of the curriculum over 18 months.

Democratic Governor Ralph Northam, who served in office from 2018 to 2022, originally wrote the standards. But when Republican candidate Glenn Youngkin was elected in 2021, he and his supporters wanted their own. After urging the board to pause the standards review process, Youngkin proceeded to completely rewrite the proposed history curriculum.

He drafted a “reframing” of History, which put more emphasis on patriotism and less on critical race issues. His original draft received backlash for not including any education on Martin Luther King or Juneteenth at elementary levels. Upon second revision, Youngkin’s standards still refrained from teaching about civil rights leader Cesar Chavez or the effects of slavery on today’s society.

The Bigger Picture of Education Debates

This debate was a part of a much larger context of so-called “history wars,” in other words, fights over how to teach and understand history. On one side of the argument are those who believe U.S. education should put more emphasis on the effects of systemic racism and historic discrimination on society today. The other side argues that schools should emphasize the U.S.’s successes, and history should reflect the country’s progress and democracy.

As is evident in Virginia, these fights are about much more than history. Public debates over how we write the American past quickly became the newest avenue for partisan debate. Republicans denounce the emphasis placed by new standards on race. They claim it represents the problems with today’s “woke culture,” and the Left. Meanwhile, Democrats accuse Republicans of sending America backward in time.

In most cases, neither side will give up until one has declared victory through a new law, removal of a monument, or a banned textbook. In November 2022, Florida, a famous example of culture wars, wrote into law the “Stop W.O.K.E” Act, which bans teaching on racial issues. This includes all topics that discuss the legacy of racism, white privilege, and subconscious biases. School districts in Florida have since banned books if they touch on “inappropriate topics,” such as LGBTQ+ and race issues.

A Long History of Culture Wars

But debates over how to frame the U.S.’s history are nothing new. Americans have been fighting over how to envision their history since the 20th century. In the 1920s, civil engineer Harold Rugg created a line of social science textbooks designed to present “a more progressive take on American society,” historian Adam Laats told Vox. Rugg’s books, which had become popular in schools, began to face backlash in the 940s. Parents burned his books, accusing him of Marxism and treason. The books quickly went from being everywhere to virtually unfindable.

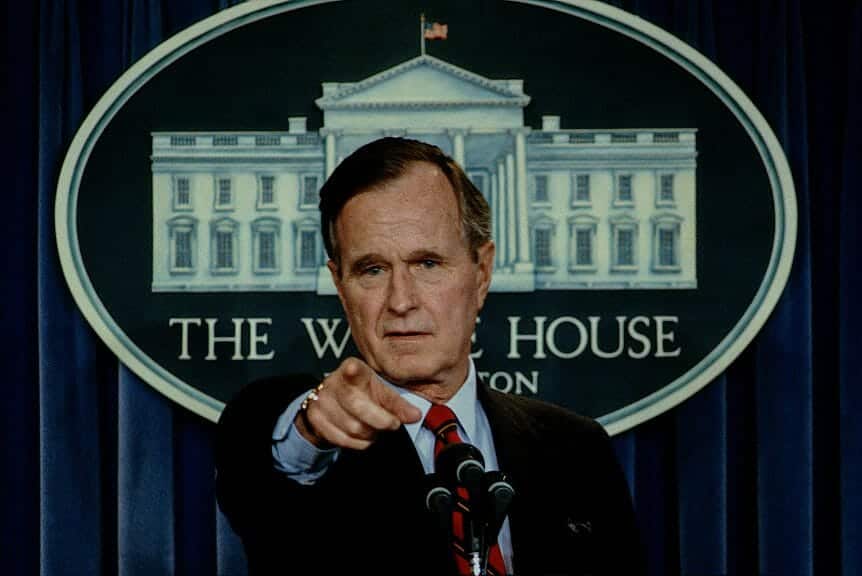

The war on history resurfaced in 1994 when George H. W. Bush decided to create national history standards. These debates were once again divided between those who wanted a celebratory view of the U.S. and those who wanted a more critical one.

Recurringly, history wars arise at times when the U.S. fears being overtaken as the world superpower. In the 1940s, when the threat of communism arose, Americans blamed the U.S. falling behind on their education system. In the 1990s, when the new threat was Japan’s booming automotive industry and developing economy, politicians hyper-fixated on history wars. Now, 30 years later, the threat is China’s economy. As the cycle repeats, many Americans afraid of outside threats consciously or subconsciously believe that propping up U.S. successes and bolstering patriotism is the key to regaining the U.S.’s spot as number one.

The Case of Virginia

It is thus easy to conclude that the U.S. will never reach a decision on the issue of history. But Virginia proved that this isn’t necessarily the case. When the more conservative draft of the history curriculum was presented to the board of education, Youngkin had built, something unexpected happened. The board voted unanimously to reject the conservative version of the proposal.

What followed next was months of public debates and new drafts, which eventually led to a set of education standards that both the left and right agreed were acceptable. It may seem odd that reaching a compromise both sides are merely “okay” with is a win to be excited about. But in the U.S. context, where Americans can no longer agree on how to teach history, which books to allow in school, or which classes to be taught at all, a reminder that we are still capable of reaching compromise may be the hope we need.

Latane Mack

September 13, 2023 at 1:08 am

Another concise article ! Thank you.