Ash-covered fingers, char on cheeks, heaps of discarded leaves, red oil from salsa de calçots’ staining the picnic bench. These are just some of the common sights at les calçotades, the barbecuing tradition that began with a 19th-century peasant in Valls, Tarragona.

Between January and April every year, families and friends come together to celebrate the calçot. Calçots are a type of green onion that may seem ordinary at first but are actually at the center of an important Catalonian custom, la calçotada. The calçots arrive at the table wrapped in newspaper and after the unfurling, what follows is a wonderfully unrefined ceremony of peeling, dipping, and slurping.

It’s easy to get lost in the laid-back rhythm of la calçotada but when I sat down with Arnau Raventós Gascón to discuss his family’s farm in Terrassa, he assured me, “There’s a lot of work behind it.”

How to cultivate calçots

Arnau has a smile on his face as he describes the steps involved in cultivating calçots and the “fun, complicated, and hard” days of collecting them that follow. Maybe it’s the mention of his late grandparents, their farm and vegetable garden, or recounting memories of cutting back towering thickets with his mother when they decided to begin a garden of their own on the land they inherited, but he seems devoted to this labor.

Among the countless items Arnau grows, from fig and cherry trees to tomatoes and lettuces, calçots were the very first. “An onion is a plant that resists,” and aside from some watering, there is little day-to-day care involved.

A step-by-step guide to growing

Arnau walks us through the process:

- Although you can decide to grow the calçots from seeds or onion sets, the easiest option is to buy mature calçot onions.

- Between the end of August and early September, make furrows for planting, and place the mature onions on top. Only surround the bulb halfway as they’ll take root from the bottom and grow leaves from the top.

- Water them, and after about two weeks you should start to see new green shoots.

- Then, you can begin to cover the onions.

- As the leaves grow higher, continue to cover them. The covered leaves will then turn white due to blanching. But, always leave part of the leaves exposed to allow the plant to breathe and photosynthesize.

- Eventually, you’ll create a small mound encouraging them to shoot upwards.

- Depending on how big or small you want them to be, start gathering them from January onwards. A digging fork should come in handy!

From every bulb planted, you can expect between 5 and 12 calçots.

What is a calçotada?

“For me, it’s the transition from the winter, the toughest and ugliest time of the year into the nicest season of the year which is spring.”

Arnau Raventós Gascón

The day you decide to pry the calçots from the soil is typically the day you have a calçotada—an “elaborate day,” according to Arnau.

Once you’ve gathered them, a tiring task, by the way, they are then washed, and about two or three fingers are cut off from the top, leaving enough for you to grab when you eat them. They are then set aside until the fire is red-hot. The type of leña or firewood used is usually small vines or branches “the size of thumbs.” A strong flame scorches the calçots and licks the outer skin black.

Although everyone has gathered in the calçot’s name, there is much more to this cultural feat. The standard ‘pica pica’ takes place while the calçots continue to simmer. It’s a customary step.

Everyone, except the designated barbecuers, snacks on olives, tortillas, and chips, and a cold vermut rojo is certainly not out of place at this point. Eventually, the more curious individuals drift in the direction of the fire to observe, some look over their shoulders, and others embrace the sunlight.

“But when is it cooked? The calçot starts to boil from the inside, to sweat little bubbles.”

Arnau Raventós Gascón

After removing them from the grill, they are wrapped in newspaper and placed on clay tiles to keep warm for at least 30 minutes. Over the settled fire, it’s then very typical to cook botifarra (a type of sausage), lamb, and other types of meat. But let’s not forget about the salsa de calçots, “the best part,” says Arnau.

Salsa de calçots: a slight misunderstanding

Often called ‘romesco,’ salsa de calçots is actually a Catalan sauce similar to romesco but prepared with a different kind of pepper, nyora (ñora).

Traditional ingredients: The base of the sauce is roasted vegetables—nyora peppers, onions, garlic, and tomatoes. Add almonds and dried fruit and blitz together. Arnau remarks, “In the end, every family makes it their own way.” Some even add milk chocolate!

Mastering the peeling technique

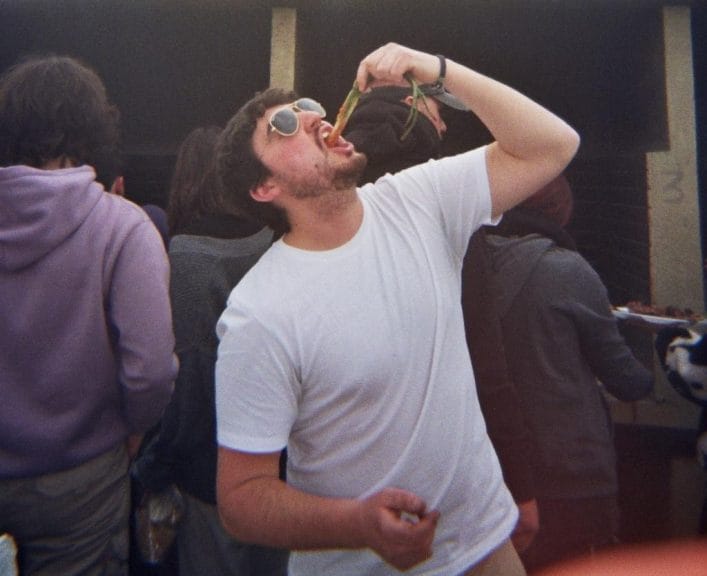

Remove the tender inner part from the sooty outer layer and plunge it into a bowl of rich salsa de calçots. There is no place for cutlery, cautious bites, or urbanity at these Catalan feasts. You simply have to embrace the mess.

Ultimately, a calçotada is best experienced out in the open air

Arnau emphasizes that a calçotada is “something typical from the countryside, so you have to go to more rural areas.” Undoubtedly, restaurants in Barcelona, Madrid, and other places around Spain serve calçots—however, the provided bibs and plastic gloves separate diners from the char and chaos. The white tablecloths and the absence of flames cannot compare to the earthy smells, rising smoke, and candid way of being at a rural masia, merendero, or family home.