Scientists were left baffled as a collapsing section of cliff face in the Grand Canyon revealed two never-before-seen sets of tracks; the oldest ever seen in the Grand Canyon, and amongst the oldest ever recorded globally. The tracks provide vital missing documentation of stages in vertebrate evolution dating back many millions of years.

The tracks, originally spotted by chance in 2016 by Norwegian scholar and geologist Alan Krill, were passed on to his fellow faculty members for further analysis, where they were confirmed to be novel. Now, over 3 years later, the findings have been officially published in interdisciplinary science journal PLOS ONE as of last week.

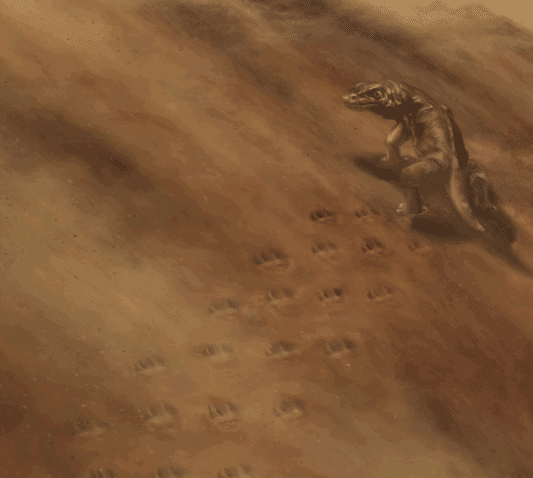

The publication suggests that the markings were left by small, four-legged animals- and not only that, but are amongst the oldest known evidence of “shelled-egg-laying animals, such as reptiles, and the earliest evidence of vertebrate animals walking in sand dunes”, Stephen Rowland, colleague of Krill remarked.

What else can we know about the creatures responsible for these trails?

Well, sadly not all too much. Such is the nature of fossil work. While breaking the record for the oldest known fossils in the Grand Canyon is no mean feat, the identity of the authors of these tracks is still unknown.

What Rowland can tell us is that the creatures moved in “lateral sequence”, meaning their four limbs would move one side at a time- much like modern-day cats and dogs will tend to do when walking slowly. This fossilised evidence is actually the oldest recorded document of lateral gait in vertebrates, a behaviour presumed yet never concretely preserved until now.

This new revelation comes hot off the heels of major news regarding the origins of Stonehenge just earlier this month, making it clear that even places presumed to be so scrutinised and well-documented can hold secrets. Makes you wonder what else is hiding out there- and if/when we’ll ever find it.