In just a few days, billions of corals bundles released into the waters of the Australian coast, filling the water with life.

Once a year, around November’s full moon, the Great Barrier Reef experiences the worlds largest simultaneous spawning event. Over the course of a few days, corals across the Western coast of Australia release spawn––eggs and sperm bundles––in unison, filling the water with life.

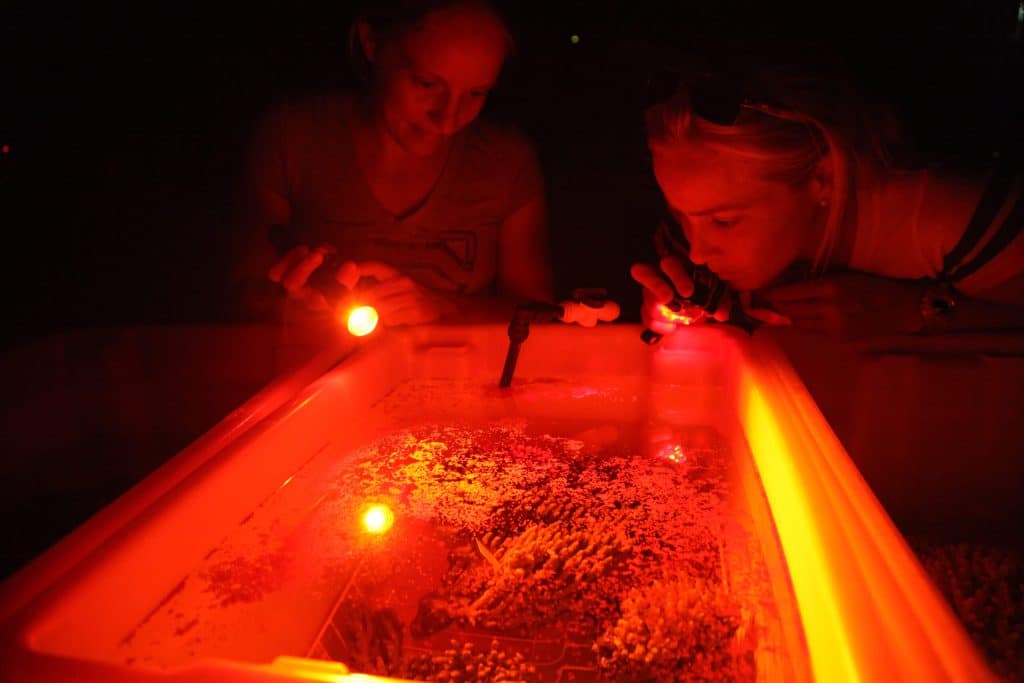

This year, the spawning event occurred on the evening of November 23rd under pristine conditions: a glowing moon and clear, still water. The full moon occurred just days before on November 19. For days following the release event, billions of these bundles surfed the currents before settling on the reef to bring life to new colonies.

While the current and future health of the reef has been a site of immense focus and concern with recent ocean and air warming trends, this year’s spawning event brings hope to scientists as it facilitates further research of heat-resistant corals.

At the Australian Institute of Marine Science, Dr. Kate Quigley works with the National Sea Simulator (SeaSim), where huge tanks are home to several different tanks filled with corals, all kept at different temperatures and carbon dioxide pressure levels (used to study ocean acidification).

The spawning of coral colonies is synchronized across the region, aligning the release of the Great Barrier Reef’s corals with those of SeaSim. During this period of spawning, Dr. Quigley and her fellow researchers worked diligently to gather spawn bundles from the water to bring into their selective breeding program which studies evolving temperature tolerances for Australian corals.

Dr. Quigley and her colleagues have been studying the possibility of gene flow across various types of corals, all with different temperature tolerances. Corals in the northern reefs, where the ocean temperatures trend warmer, can tolerate higher water temperatures without experiencing a stress response or bleaching event. Southern reefs, where the water is colder, have reduced temperature tolerance, making them more vulnerable to rising temperatures.

In 2020, Dr. Quigley’s team collected hundreds of corals they suspected to be heat-resistant based regions that survived the mass bleaching events of 2016, 2017, and 2020.

Their plan is to breed these heat-resistant corals with the more vulnerable corals of the southern reefs. This process is called gene flow, and Quigley’s project is to accelerate it. In the SeaSim tanks, researchers can monitor how well the corals survive and grow––if their project was successful.

In spite of the increasing stress of climate change on the coral reefs, many scientists retain hope for the future of coral reefs, both in the Great Barrier Reef, and globally. Marine biologist Gareth Phillips called this year’s spawning event “a sign of hope that it’s doing well, and we need to keep protecting it.”

However, the coral reefs’ still require urgent attention. In the years between 2009 and 2018, the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN) estimates that the world lost 14% of coral reeds globally to rising tea temperatures.

Recent years have seen significant damage to the plant and animal life of the Great Barrier Reef, with significant bleaching events triggering mass chain reactions across the ecosystem. When water temperatures rise beyond a certain threshold, corals eject the algae that they have a symbiotic relationship with in order to sustain themselves via photosynthesis. Without these algae providing them food, corals quickly starve to death.

Coral reefs are extremely valuable to sea life; although they only comprise 0.2% of the seafloor, they support more than a quarter of all marine life and provide the base for the entire ocean’s health.

Considered one of the seven great wonders of the world, the Great Barrier Reef is home to over 3,000 individual reefs of over 400 different species of coral––the world’s largest collection of corals. It spans over 1,800 miles (3,000km) of Australian coastland and is home to a number of endangered species, including the Sea Cow (Dugong) and the large Green Sea Turtle.

Interested in reading more about the latest environmental updates? Click here to read about the California condor’s parthenogenesis.