The old question of whether art imitates life or vice versa often produces fascinating answers. As we have become more aware of the effects and dangers of capitalism, especially in more recent years, cinema has reflected these ideas. As a result, an interesting subgenre of film has emerged: anti-capitalist satire.

Many films have anti-capitalist themes and messages. Just look at Jordan Peele’s latest film, ‘Nope’, which has an anti-capitalist metaphor at its center. But the anti-capitalist satire is its own thing – it takes the absurdities of capitalism and reflects them back at us through satire in ways that are undeniable.

(Spoilers ahead for all the films I discuss!)

‘Office Space’ (1999)

The film at the center of this subgenre is 1999’s ‘Office Space’. It’s one of the first and possibly the purest example. It stars Ron Livingston as Peter, an office worker who really hates his job. After some hypnosis gone wrong, he decides he no longer cares about work, and proceeds to make a mockery of both his office and the system of capitalism in general. In the film, we are repeatedly shown the tedium and bureaucracy of the office and the exhausting effect it has on Peter in particular. Although the workers dislike their jobs and feel drained by them, they fear being fired at any time at the whim of their boss, Bill Lumbergh. Lumbergh enjoys flaunting his power over the workers. Each week, he orders Peter to come into work at the weekend, ensuring that he has very little time off and that his life pretty much revolves around his work.

Also in the film, a waitress named Joanna is constantly in trouble with her boss for not having enough ‘flair’ – simply, badges on her uniform. He agrees that she technically has the minimum amount of ‘flair’, but asks why she doesn’t want to take the opportunity to “express herself” at work. This is clearly a metaphor for bosses’ unrealistic expectations for their employees, who believe that the workers should want to go above and beyond and do more than they’re supposed to, even though they’re only being paid minimum wage.

Later, Peter and two of his colleagues plan to install a computer virus that will take lots of small amounts of money from the company and put it into a separate bank account, which adds up to a lot of money over time, but will be undetectable. This can be seen as a reference to how workers only ever make a fraction of what a company makes, and that in a way, these characters are taking what they’re owed.

The plan ultimately goes wrong, but before they face any consequences, they find that their office building has been burned down by another employee who’s sick of being mistreated by the company. This is a cathartic ending – the source of the characters’ pain and frustration has been symbolically destroyed. And even though the capitalistic system lives on, the characters find ways to get by, leaving us with hope for their futures.

‘Office Space’ is undeniably a satire. It reveals the absurdities of the systems of capitalism and the office workplace by replicating that absurdity inside its story. For example, Peter uses the wrong cover sheet on a report, and proceeds to be told by several managers that he did so, and that he should use the right one from then on, and that he should really look at the memo explaining it, and they’ll send it to him again – even though he clearly has the memo in front of him on his desk.

An iconic image from the film shows the whole office standing around in front of a banner that reads, “Is This Good for the Company?” We could all easily imagine nearly every company nowadays imploring their employees to consider this question before doing anything. It’s no wonder ‘Office Space’ is still so significant a film more than twenty years later, and that it marked the beginning of a new cinematic subgenre.

I see ‘Office Space’ as being a particularly significant example of this subgenre because it’s an anti-capitalist satire through and through – its themes and message are very clear, and it’s not interested in tackling any other themes or issues. For the most part, however, films in this subgenre take varying perspectives on this idea, and look at how capitalism intersects with other issues.

‘American Psycho’ (2000)

Mary Harron’s film ‘American Psycho’, adapted from Bret Easton Ellis’ 1991 novel, was released only a year after ‘Office Space’, but it already demonstrated the variation on the theme that filmmakers would continue to lean into over the next twenty years. This cult classic follows Patrick Bateman, an investment banker who lives a violent double life. The film is set in the 1980s and satirizes the culture of Wall Street and the ‘yuppie’ (’young urban professional’) figure that was prominent at the time. This is all framed through the perspective of Patrick, who symbolizes a particular kind of person formed by the capitalistic system, and whom Harron comments on.

The iconic business card scene is a great example of how Harron satirizes the ridiculous rituals and oneupmanship of Wall Street, which is a symbol for the capitalistic system in this film. A lot of tension and drama is created in this scene merely by Patrick realizing that his colleagues’ business cards are better than his. This is a clever way of conveying how odd the situation is: the guys who are making a lot of money off other people’s hard-earned money are really only concerned with their status, especially in relation to their peers. But she’s also making fun of these men with so much power and money – they’re really quite pathetic.

Harron takes an interesting perspective on this theme. While these Wall Street men, who are representative of all the wealthy people who benefit from capitalism, are powerful and dangerous (as Patrick is), they’re also pathetic. They’re so desperate to seem impressive that they pretend to wrangle a reservation at the most exclusive restaurant. They fret over how their business card compares to that of their colleagues. More powerful and respected men constantly mistake them for someone else. The reveal at the end of the film, that Patrick never really committed any of these brutal acts of violence, that he just imagined it all, is just the cherry on top.

‘Knives Out’ (2019)

In 2019, Rian Johnson fused the anti-capitalist satire with the murder mystery subgenre. In the film, a private detective investigates the murder of the patriarch of the very wealthy Thrombey family. The story is told from the perspective of the victim’s nurse and close friend, Marta Cabrera. Marta and her family are immigrants to the US, and her mother is undocumented – a fact that the Thrombeys are aware of and later use against Marta. A running joke in the film is that none of the family members know where Marta is from, always naming a different South American country.

The Thrombeys claim throughout the film that Marta is “part of the family” – but, of course, she’s not, she’s working for them. Johnson cleverly conveys this dissonance by first showing one of the characters describe Marta as such, over a flashback where he beckons her over to join the rest of the family. However, we later see how this scene actually played out – he was really beckoning her over to support his anti-immigrant point. The family don’t see Marta as one of them, they just describe her as such in order to mask their exploitation of her.

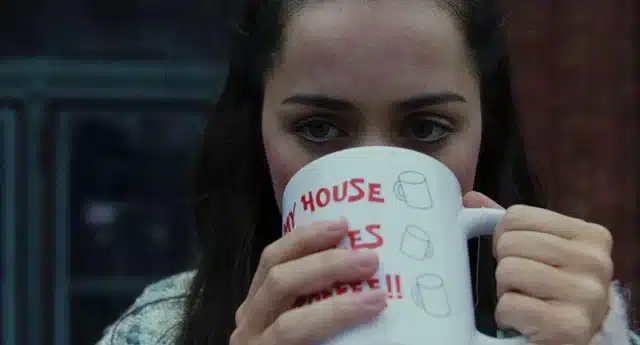

Like ‘Office Space’, ‘Knives Out’ has quite a cathartic ending. The patriarch has left everything to Marta in his will, and now the Thrombeys, who have known nothing but wealth and privilege their whole lives, have no mansion and no money. However, Marta, who was genuinely kind to Harlan and treated him like a person rather than a source of income, and is described throughout the film as “a good nurse, ” inherits everything. The powerful final shot of the film shows Marta looking down on the family from her new balcony, holding a mug that reads: “My house, my rules, my coffee”.

‘Sorry to Bother You’ (2018)

Boots Riley’s debut feature film ‘Sorry to Bother You’ is the clearest example of an anti-capitalist satire from the last few years. It’s similar to ‘Office Space’ in that the entire plot revolves around the system of capitalism and how it harms workers. But Riley also explores how racism is intertwined with capitalism.

‘Sorry to Bother You’ stars, LaKeith Stanfield as Cash, a call center employee who rises through the ranks by using a ‘white voice’ to talk to customers. Once he’s at the top, he turns his back on his fellow workers, but also learns about the sinister inner workings of the company. The film explicitly conveys how racism and capitalism are connected – the only way for Cash to succeed in this world is to use a white voice, sacrificing his Black identity. Elsewhere in the film, Tessa Thompson’s character Detroit explains her art show about Africa by saying that she wanted to talk about “how capitalism basically started by stealing labor from Africans”.

Although ‘Sorry to Bother You’ is similar to ‘Office Space’ in terms of its intention and message, its execution is very different. Riley blends the anti-capitalist satire with science fiction. Late in the film, Cash and the audience discover that the company he works for is turning workers into human-horse hybrids to create more efficient, productive workers. This is a clear metaphor for the exploitation of workers under capitalism, how companies are always looking for ways to increase productivity, neglecting to consider how it’s real people who are doing the work. The absurdity of this situation is one of the aspects that makes this film a satire – Riley is going to extremes in order to get his message across.

What is This Subgenre Trying to Achieve?

What all of these films and the subgenre as a whole are trying to achieve is to inspire us to think critically about our own capitalist society. They want to start a meaningful conversation to raise awareness. But these films are all successful because they’re entertaining and thought-provoking. They’re successful as films, because they’re enjoyable to watch, but they also mean something. After all, isn’t this the point of art – to entertain, but also to create something meaningful that makes us see the world from a different perspective?