Elvis has (re)-entered the building with Baz Luhrmann’s new biopic – but what danger does the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll hold for the 21st Century?

Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Elvis’ seeks to expose the corruption and tragedy at the heart of Elvis’s meteoric rise. To do so, it pits Elvis (Austin Butler) against Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks) – Luhrmann’s Machiavellian villain. In this regard, Luhrmann hits all the expected notes. Elvis is the unequivocal victim; Parker is his malignant overlord. And yet, the biopic has a dangerous undercurrent. By establishing Elvis as our glorious Rock ‘n’ Roll king, Luhrmann sidesteps the much darker aspects of Elvis’s career.

To date, some of the most contested aspects of Elvis’s life and legacy are his marriage to a young Priscilla Beaulieu and the heavy presence of Black music in his discography. Both of which Luhrmann deems fit to undercut. The former has no real mention in the film. And the latter amounts only to a sort of pandering. Luhrmann’s seeming desire to depict Elvis as a patron of Black culture and music wins – he is (note) not a thief.

The danger here is that Luhrmann’s movie disregards some serious issues. And that he does so in the name of sanitizing a celebrity. Luhrmann unblinkingly plays into celebrity culture, placing Elvis on an insurmountable pedestal. Such an issue has perhaps never been more relevant in cinema than now, as a slew of biopics – both recent and yet unreleased – beckon from the sidelines.

Elvis and Priscilla’s Relationship

The union of Priscilla and Elvis is one couched in scandal – and for good reason. Their first meeting occurred when Priscilla was only 14. Then, the junior to a 24-year-old Elvis by 10 years. But Luhrmann’s film seems immune to the scandal. It finds in Elvis and Priscilla’s relationship only love.

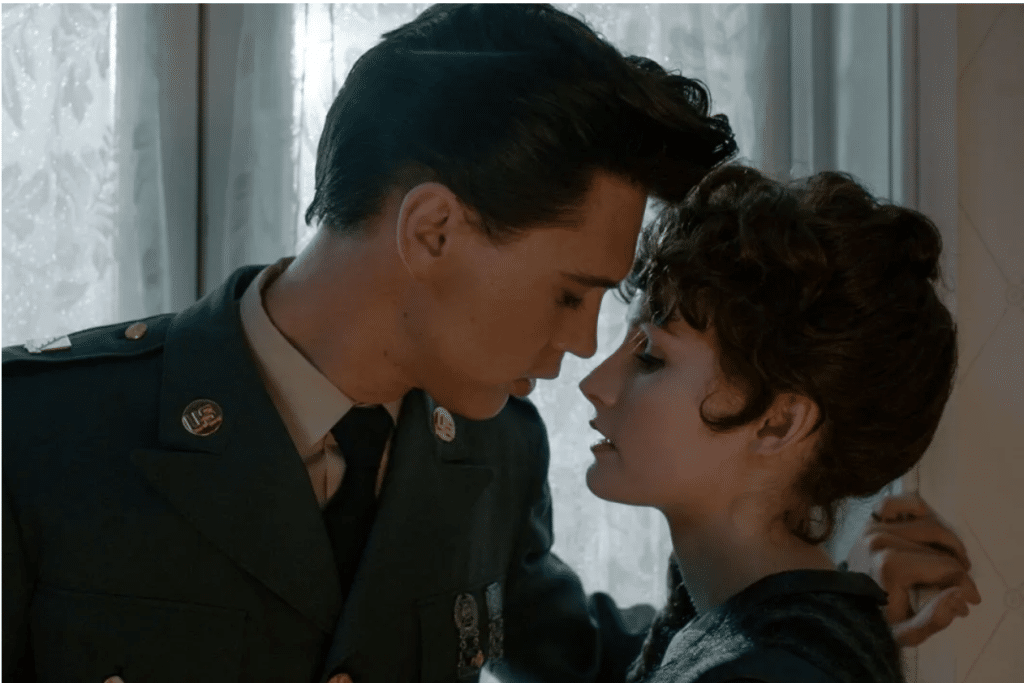

The introduction of Priscilla (Olivia Dejonge) is unsuspecting. Luhrmann cuts to Elvis and Priscilla in West Germany, engaging in pleasant conversation and good music. The scene is suspiciously neutral. It holds nothing beyond a kiss. There is no mention of Priscilla’s age, nor Elvis’s quite immediate (and inappropriate) pursuit of her. In fact, the continuity between Dejonge’s 14- and 21-year-old Priscilla lulls the audience into a false sense of security. Luhrmann tries to assure us that there’s nothing to see here. At least, nothing beyond the tender burgeoning of a relationship between two twenty-somethings.

This is largely untrue. Priscilla did meet Elvis in West Germany. And Luhrmann rightly touches on Priscilla’s relocation there in the late 1950s due to her step-father’s airforce position. The result of which was an inevitable exposure to the soldiers on base – to Elvis. By Priscilla’s own recounts, however, Elvis was hasty in romancing her despite her age. Something Luhrmann conveniently skips over. In her 1985 interview with People magazine, Priscilla recounts Elvis asking after her age, and his reaction: “Why, you’re just a baby.”

This whole interview reads as perverse. Looking back, Elvis’s own protests that he’d “treat [Priscilla] just like a sister” were clearly in vain. After meeting for only the third time, Priscilla recalls Elvis inviting her to his room – and later, kissing her. Their grossly inappropriate relationship developed at his behest. Priscilla was led by Elvis. “He wanted to mold me to his opinions and preferences”, Priscilla remembers. From that same room on base that we see in the film, Priscilla was drawn into something sinister.

Luhrmann – quite worryingly – treats this as insignificant. His biopic doesn’t relate to this eery first meeting. And after their marriage in 1967, Luhrmann soon hurries back toward Elvis’s career. This makes his heavily sanitized version of their union categorically dangerous. It sees fit to ignore abuse in the name of glorifying Elvis. Indeed, whilst Priscilla has never publicly acknowledged Elvis to be abusive, his actions clearly read as perverse. Luhrmann seems to qualify that such is ok – as long as it’s done by a talented white man.

Elvis’s Legacy with Black Music

Elvis’s discography is one of the most contested aspects of his career. And largely because it is saturated by Black music. The singer has accrued a lot of criticism that he profited off the works of Black artists.

In some respects, Luhrmann does attempt to acknowledge this. Elvis’s connection to Black music and artists features quite heavily in the film. His hometown of Tupelo is a frequently-visited location. And Elvis is often shown enthusiastically listening to Black music – both as a young boy and in his later life. One scene depicting an enamored Elvis enjoying Little Richard’s performance of ‘Tutti Frutti’ stands out. And throughout the film, he even finds a good friend in fellow musician, B.B. King.

However, Luhrmann seems to be indelibly stuck to a sort of Elvis-mysticism in his movie. He lauds the singer as a unique conduit to a spiritual Blackness. One which seemingly enables him to best disperse Black music across North America. Luhrmann literally envisions Elvis as a host for Blackness. In Tupelo, a young Elvis enters a Black Pentecostal tent service. Its music sends him into a spell. He is urged by some deep instinct – by an inherent Blackness – and writhes on the ground.

So, Luhrmann sees Elvis as some kind of white oracle. It follows that, both in the film and in reality, Elvis profited off of much Black music. His famous hit ‘Hound Dog’ is one example – an infamous cover of Big Mama Thornton’s song, for which she allegedly made only $500. It is even more incriminating that Luhrmann only really features Black artists – Little Richard, B.B. King, and Big Mama Thornton – in a shallow way. They act as props to Elvis’s (white) exceptionalism – as moments of revelation, or opportunities for profit. Luhrmann never commits to the Black artists in his film. Black excellence is devastatingly side-lined.

Even the film’s featured song, Doja Cat’s catchy ‘Vegas’, plays for much less than a minute in-film. Used in much of the biopic’s promo, it interpolates a sample of Big Mama Thornton’s ‘Hound Dog’ and interrogates Elvis, the hound dog himself. It seems to prove that Luhrmann’s dissection of race is merely superficial.

Conclusions

Luhrmann’s film is but a half-baked attempt to dissect the infamous King of Rock ‘n’ Roll. His glitzy, saccharine world proves only that it wishes to pander to Elvis. And so, Luhrmann exhibits the danger of the biopic. In seeking to sanitize the world’s best-selling solo artist, Luhrmann exposes the way in which prejudice and abuse can be even further side-lined. And given the ever-growing rise of biopic cinema, his film holds a great lesson for cinema – and us all.