Ahhh, TikTok. Whether you love it or you hate it, it’s hard to deny its effect on the music industry. Artists like Noah Kahan have gone from tiny rooms to selling out arenas simply because seconds of their music has gone viral.

Lovejoy

A prime example that comes to mind is the indie-rock band Lovejoy, which rose to massive success following the pandemic. You might mistake them for the average sweaty, try-hard indie band pumped full of dark fruits and “they’re called the Arctic Monkeys, you might not have heard of them…” but these guys have something that a lot of other bands don’t.

A chronically online fanbase.

Now, I’m not a person who uses ‘chronically online’ as a derogatory label, as people are wont to do. Lovejoy’s viral intensity warrants this term arguably more than any other band in existence. Before their first-ever gig, they’d amassed millions of streams and YouTube subscribers. Frontman Will Gold became a Gen-Z household name through successful streaming within a few short months. They played their first gig under the pseudonym ‘Lamp with Sock’ simply because they wanted no one to find them.

They sold out tickets for their first-ever tour within seconds. Fans lined the streets for hours during their first festival (Neighborhood Festival in 2022), only for most to leave disappointed. But, lacking the experience most bands already have, they faced one issue. How the hell do they live up to this massive name they’ve created for themselves?

The world of YouTube stars

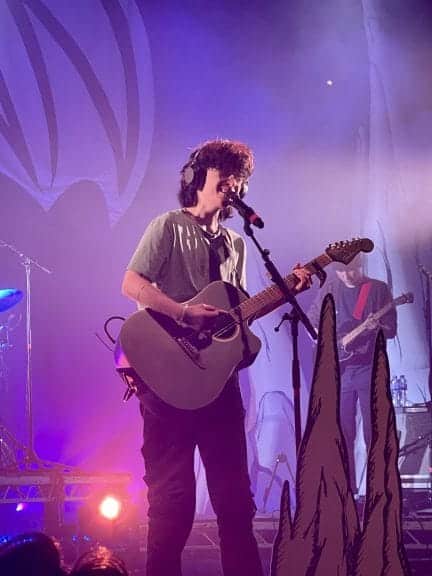

Cavetown provides another prime example of this. His astronomic rise has been more of a slow burn than a COVID-era rocketing to fame. He began posting on YouTube as a young teen, rising to online popularity ever since. With a following in the millions across social media platforms, Cavetown is closely associated with other such ‘online’ artists, such as Chloe Moriondo, Dodie, mxmtoon and Tessa Violet, who also began their music careers with a simple YouTube channel.

This sphere of indie artists emits positivity and has provided a safe haven for queer teenagers across the globe, who find solace in their soft vocals and honest songwriting. Ricky Montgomery, who toured with Cavetown and mxmtoon last year in the hugely popular ‘Bittersweet Daze’ tour, experienced a huge blowup online following his songs ‘Mr Loverman’ and ‘Line Without in a Hook’ going viral on TikTok. The examples of these musicians are endless, and this is just within a certain subgenre.

TikTok has completely changed the way we view social media; the way we consume our music has been permanently altered. With over a BILLION users, its impact on charts and on artists is insurmountable. It doesn’t necessarily render record labels obsolete, but the way consumers can access music has changed. Independent artists now have access to a global market and can reach thousands with a single video. A song can go from a hundred Spotify streams to a hundred thousand almost overnight.

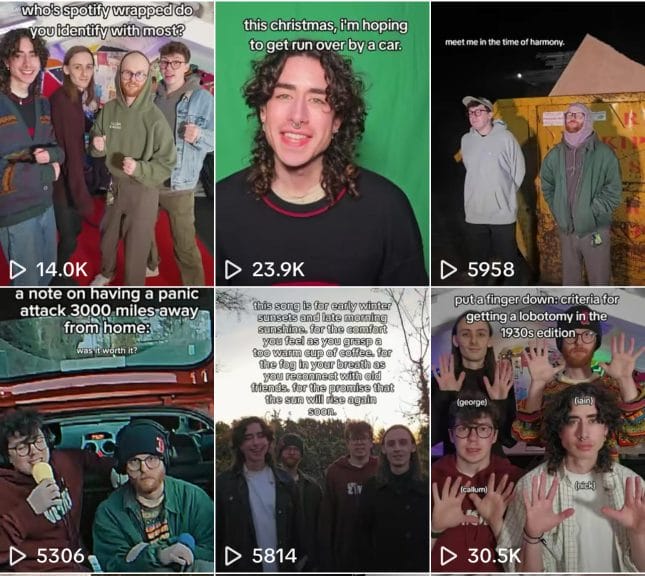

Bears in Trees

Social media, particularly TikTok, has altered the careers of many artists. Bears in Trees are a four-piece, self-proclaimed “dirtbag boyband” hailing from Croydon in the UK. 2020’s lockdown hit as they prepared to release their EP I Want To Feel Chaotic, marking a whirlwind ever since. Guitarist Nick Peters (he/him) was kind enough to sit down with me to discuss TikTok, online fandoms and growing up on the internet alongside the band’s bassist, Iain Gillespie (they/them).

The first time I saw Bears in Trees, they were performing at Manchester’s Bread Shed during their inaugural tour. Still, in the midst of the COVID pandemic, I remember being drawn to their raw lyricism and honest online presence in and among all of us being locked in our houses. The crowd, being absolutely tiny, had an incredible atmosphere. Buzzing to finally see the band we’d all found over lockdown.

It would be a mistake to say that the people sitting in front of me haven’t changed at all, but that unflinching honesty and earnestness have remained steadfast throughout the years. Having released their debut album And Everybody Else Smiled Back in 2021, and two subsequent EPs, they show no sign of stopping any time soon. They first began their TikTok in early 2020. Since then have amassed over half a million followers. A lot of the fanbase is online, spanning across the globe.

The sandbox

Nick smiles when I ask him about his views of the term ‘chronically online’. “I suppose it can be a term of endearment when used by the right people,” he says, “I would never want to weaponize it or use it in a way that would make anyone feel negatively towards their passions.

I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with being proud of being chronically online if that’s what people want to call themselves. Especially post-COVID, y’know, that’s how people interacted with one another. I think our views as a society have definitely shifted recently. It’s the way communication is moving, and there’s nothing wrong with it if it’s used by good people.”

The Sandbox refers to the collective name for Bears in Trees fans. It’s coined from their first album, Just Five More Minutes. It spans Discord, X, Instagram, Tumblr – basically, any social media platform you can think of. The community really came together during the Covid pandemic, showing support for both the band and one another during the long periods of lockdown. It’s a succinctly modern experience, finding bands you love and connecting to them through social media posts. It#s not just a post-2020 thing, either.

The conversation shifts to past experiences with online fandom. Particularly in the alternative scene, with bands such as Fall Out Boy and My Chemical Romance, there is a longstanding past with fandom spaces existing on sites such as Tumblr or AbsolutePunk.net. It is within these spaces that many modern artists have their roots. Of course, Bears in Trees are no exception to this.

“When we were growing up and in fandom ourselves,” Nick looks over to Iain and grins, “back when Facebook was still a cool thing to use, your face wasn’t visible. You were hidden behind the aesthetic that you chose to curate. What you wore and how you presented yourself never really came into the equation.”

Considering reels and TikTok, he continues on to discuss the very visual element of these platforms. “The content you see, and because of how it’s presented, you’re naturally gonna drift towards dressing that way, or at least presenting yourself in a way to align with the subculture, and there’s a certain pressure on people to do so. When we were younger, you didn’t have to do that. You had time to develop your style, and you didn’t have to show that to the world.”

Social media platforms are full of insanely niche aesthetics. ‘Rain-core’, ‘clean girl aesthetic,’ ‘cottage-core,’ ‘weird-core,’ ‘corporate-core’ – there is literally no escaping it. From the moment you sign up to a social media platform, you immediately have to curate your own aesthetic. It’s an epidemic.

He continues – “going from being a band mostly known for shitposts on Tumblr and Twitter, things very quickly shifted to who we are. What we look like, what we wear. It’s funny when we look back at fan art because you can tell when it was. Callum (BiT’s vocalist and resident ukulele player) might have space buns. George (the drummer), well, you can tell by the length of his hair. Iain might have a mullet. There’s a much greater awareness of your body as an art piece.”

Iain nods. “There’s a pressure to be a perfect version of yourself. You have to be a complete finished product as opposed to a work in progress.”

Flanderization and the pressures of visual culture

What arises from this visual culture is a strange juxtaposition between being hyper-individualistic (‘me-core’) yet simultaneously forcing one’s self into a tiny little box to align with whatever extremely narrow trend is going viral that week. TikTok and Instagram reels are methods of perpetrating this culture, and it seeps into fandom and every other corner of the internet. Gone are the days when one can be anonymous. To be successful online, you cannot be faceless.

And then there is the issue of being authentic. How does one balance the act of being authentic with projecting this perfect image of yourself?

“We talk about that weekly,” Nick says, “who we are changes so much. We are different than we were two or three years ago when we started blowing up. And people still have that image of us in their heads. Not that I blame them because that perception isn’t necessarily wrong. It’s just not us anymore.”

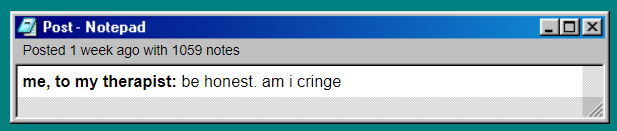

He then asks if I’ve heard of the term Flanderization. (Of course, I haven’t.)

Flanderization, in its simplest terms, refers to a complex character whose traits are oversimplified until they become a comical approximation of who they once were. Specifically, it refers to the Simpsons charcater Ned Flanders. He transitioned from a good-hearted, Christian neighbor into nothing more than a dogmatic Bible basher.

Iain suddenly appears in the corner of the screen, following Nick, establishing that this process can also happen to celebrities and influencers.

“I’m editing our YouTube thumbnails from a few years ago, and I can viscerally tell when I was experimenting with a particular idea or style. But this is now cemented as a permanent fixture of my being.”

“It’s weird!” Nick agrees, “When we’re just making a silly little thirty-second video, I don’t think about how it might get four million views or that people might start referencing it to me. It’s weird to know that this is how I might forever stay in some people’s minds.”

In terms of marketing, I was wondering to what extent ‘growing up on the internet’ impacts how they market themselves. “It definitely does,” Nick nods, “if we hadn’t been in fandoms and making shitposts and stuff, I don’t think we’d be doing anything similar. It means that when we’re trying to curate our community, we can shape it into a space that we would have wanted when we were younger. And I don’t think that will ever change. Hopefully, we can get better at it as we learn to navigate.”

“It’s strange to go from being in those spaces to having them dedicated to you. It’s very much out of our control, but I think the best we can do is be honest. When people see you in a certain way, it’s best to be kind and respectful. It’s weird because we still meet people that we once admired and very much still do. We are lucky enough to call some of those people our friends. That feeling of having someone on a pedestal, it’s really hard to get away from that. If that’s how you saw the world growing up, it’s hard to get away from that. Putting people on a pedestal isn’t necessarily healthy, but I think we very much try to be mindful of what it’s like to be younger and have those people that you respect.”

Algorithms and Inspirations

Moving the conversation onto TikTok, they share an anecdote of being recognized in a Café Nero when the barista was watching one of their TikToks right before they walked in. I ask Nick about his inspirations for their TikToks due to their uniqueness.

“I guess it’s a combination of what we find funny and what has worked before. We use in-jokes and stuff we’ve seen online, partly what we’ve seen work before and partly experimenting with new stuff. I always try and dissect what kind of things I find funny, like if I see a meme on Instagram I’ll think about what made it funny to me. The inspiration doesn’t come all at once; it’ll just come to you before you’re going to sleep, or it’ll click when you’re watching TV.”

Trying to please the algorithm is difficult. One consequence of the massive rise in internet artists is those who curate their songs, or at least part of them, so that the twenty-second snippet they post will send them viral. You see it all the time – “Have I just written the song of the summer?!” and then it’s the same generic pop song you’ve heard fifteen times before.

I ask Nick if Bears in Trees have ever done anything like that, and he’s straight to refute that idea. “We’ve never done that. We wouldn’t be comfortable doing that. But for singles and songs we wanna promote, we try and choose the right snippet that we wanna push. It’s obviously hard to try and gauge which parts of a track will go viral, but we try and choose a really hooky bit and then a part that’s more lyrically dense.”

It’s a weird consequence of TikTok, one that I don’t think anyone could have really predicted. Its impact on the music industry is unparalleled.

Returning to Noah Kahan for a moment, TikTok went viral with his song ‘Dial Drunk’ in early 2023. This was just before he released Stick Season (We’ll All Be Here Forever), the extended version of the album he had released in October 2022.

His rise since then has been off the charts (haha) as he’s collaborated with huge artists such as Hozier, Post Malone, Gracie Abrams and Lizzie McAlpine. He’s been nominated for a Grammy, headlining huge festivals and playing London’s famous O2 arena in August, for two consecutive nights. All because of a TikTok snippet.

A less extreme example would be the Merseyside-based band Crawlers. They went viral with their 2020 hit ‘Come Over (Again)’ after a snippet of it was posted on TikTok. Since then, it has racked up over fifty million streams and earned them a shiny record deal with Polydor and a support slot for My Chemical Romance in 2022.

“As a platform, it cares about artists as much as the industry” – TikTok and The Music Industry

As for its overall impact on the industry, the opinions on the matter seem to vary. Nick, when asked about his opinions on it, nods thoughtfully. “I think overall positive. The democratization it allows and the fact that a small artist can have a massive hit is incredible. We wouldn’t be where we are without a platform like that. It’s tough because it does require you to put more of yourself out in front, and you’re kinda forced to do that.”

He asks Iain to think of any negatives, who laughs from off-camera. “I can always think of negatives!”

“It’s not necessarily negative, but when it comes to how technology has impacted music, TikTok is just a Thing that is happening. It’s not necessarily positive or negative because music is always just a reflection of the people and the culture of that present moment. That being said, I do think that with short-form video content being the primary way people consume media, it’s leading to a lot of musicians putting their entire lived experiences on the show, as well as their emotional ones. People aren’t just consuming the music anymore, I mean, they do, but much more is on show. Much more is being consumed. I’m not sure if I dig that all of the time. I mean, I get it. Years ago, I would find out everything I could about Modern Baseball or The Front Bottoms, but now it’s just a little bit easier.”

“However, the negatives are much more on the lived experience of the artist as opposed to the ways in which music is created or the way it is enjoyed and the people that consume it. The emotional state of the artist is different.”

Myself and Nick agree with them. “TikTok as a platform cares about artists as much as the industry does. Labels all have their shares in TikTok, and vice versa.” Nick shrugs, “It’s just another part of the industry.”

It’s something that the fans on the other side of the screen rarely get to see. Social media, without sounding too cliche, is making us perhaps too connected with one another. Users can perceive and judge every single detail of another’s life. It’s extremely easy to do so. People have to emerge a perfect version of themselves in every sense of the word.

While TikTok makes music more accessible, questions must be raised about the ethics of consuming a person rather as opposed to their art. It’s sometimes a very thin line to cross, and it can be dangerous to do so.

But it’s not all doom and gloom.

As previously mentioned with Crawlers, TikTok serves as a method for getting small artists in front of record labels in ways that could never have been achieved before.

Boston record label Counter Intuitive signed Bears in Trees in 2020, having also signed artists such as Prince Daddy and the Hyena and Mom Jeans. CI found them through TikTok, so I’m inclined to wonder if they think they’d have been signed without it.

“No. It’s tough because Jake (Sulzer, founder of the label) found us through a TikTok video, and we weren’t even trying to reach him. We weren’t a live band. We couldn’t have made our name as a touring band because we were all at uni. And we’re not that kind of people. Even before TikTok, we tried to do YouTube vlogs because that’s what we grew up with. But we could never quite nail it.”

To round everything off, Iain discusses the headspace they’re in when approaching TikTok and fandom.

“We’re in our mid-twenties approaching our late twenties, and as you get older, the way you experience the internet changes because it is so youth-heavy. It’s just one of those things. But we’re at that weird age of being too young to be in some spaces and too old to be in others. It creates a weird tension that would be fine if we were simply creating music, but when you’re putting your entire self out there, it can be hard.”

When speaking on the hate they get occasionally in their comments section, Nick chimes in. “If you hate what we do, it’s an example of how annoying millennials can be. But if you like what we do, it’s that this is what is cool about Gen-Z. We’re in that weird middle bit between the two. But I don’t really linger on it because people will level anything against you to justify their own pre-existing opinions.”

Conclusion

Online fandoms have existed online for as long as the internet has, especially for those who are not inclined to listen to mainstream artists. Sites such as Tumblr and Twitter (X) are ideal places for those with similar interests to mingle and talk about their shared love for a band.

There is nothing wrong with it, not in the slightest. That is, unless online fandoms are weaponized, as Taylor Swift has often been criticised for doing. (Although, considering a lot of this criticism has come from those who are not particularly fond of her, such as Scooter Braun, perhaps this should be taken with a pinch of salt).

They’re not always bad, and they’re not always good. But what’s important is that these online spaces allow bands to share their art. And, in turn, they allow fans to rejoice in spaces that make them feel welcome. Isn’t that what music is all about?

With special thanks to Bears in Trees for their input, and their kindness and honesty displayed throughout this piece. You can check out their newest release, Bart’s Bike, here.

Sue Barwise

January 20, 2024 at 5:40 pm

Brilliant Holly x

moon

January 20, 2024 at 7:28 pm

yooooooooooo

Adi

January 21, 2024 at 1:41 pm

This is such a remarkable text! Thank you for writing and sharing it! I really appreciate how insightful and genuine it feels! Great job!