Despite what TV Halloween specials and grisly horror movies may show you, cemeteries are not scary. In reality, you won’t spot ghouls or zombies walking the grounds. Coming across a cautious deer or an ornate mausoleum is much more probable.

In fact, cemeteries are at the heart of a place. Try looking at it like this: cemeteries as spaces for picnics or peaceful morning runs, headstones as keys to your family’s genealogy, and towering monuments as symbols of the local architectural style. That’s why visiting a cemetery is on the itinerary for every trip I take.

A Grave Encounter

I’ll admit, I used to be one of those people who grimaced at the thought of wandering through tombstones. I saw cemeteries as desolate — after all, they are full of dead people. Then at 17, I traveled to Guanajuato, Mexico with the Spanish language program at my high school.

On the last day of the three-week trip, students were set free to explore the Panteón de Santa Paula. It’s an inviting local cemetery where vibrant floral offerings and wreathes adorned nearly every grave. I walked along the tall mausoleum wall and read name after name in a seemingly endless array of square niches. Basically, the place made me think, “Wow.”

With just a name, birth date, and death date, you can learn a lot about someone. You can see that they lived 30 years longer than their spouse and never remarried. You can learn that they were a beloved child or devoted parent. After that day, I found it fascinating. Suddenly, I had become a tombstone tourist.

Taking on Tombstone Tourism

If you want to be a tombstone tourist — in fancy terms, a taphophile — there’s one simple first step. Pick a cemetery. Cemeteries can range from huge stretches of land with their own lakes and chapels to small family plots. Some graveyards have strong ties to a certain ethnicity or religion. Some are even dedicated to a community’s pets. There’s really no way to go wrong.

“Put on your comfiest shoes and wander,” says headstone cleaner and content creator Katie DeRaddo. “Maybe you’ve seen an interesting headstone as you’ve driven by a local cemetery. Take a few minutes and go see it up close. There might be even more interesting details you can’t see from far away.”

DeRaddo’s interest in cemeteries began with researching her own family genealogy. Then in 2020, she saw TikToks of other genealogy-inclined folks visiting local cemeteries, cleaning up headstones, and discussing the departed. How intriguing. It wasn’t long until she took up the hobby herself. A while later, after some encouragement, she started sharing her own videos.

“At first, I was hesitant to bring my work to social media because I felt it was an already saturated market with other historical videos and cemetery work, so I was content with just sharing my headstone photography on Instagram,” DeRaddo says. “It wasn’t until a friend suggested I branch into creating videos that I took the leap and started focusing on content creation.”

From Tomb to TikTok

Under the username @agraveattraction, DeRaddo has built an audience of 78K Instagram followers and 16K TikTok followers. And she’s right about the wave of cemetery content on social media. Search “cemetery” on TikTok, and you’ll see thousands of posts, from headstone cleaning to rumored hauntings to sentimental tributes to architectural appreciation.

Watching moss and grime get washed and brushed away from old, forgotten headstones inspires peacefulness. Then when you scroll, it’s shocking to hear the urban legends surrounding some graves. There’s something in cemeteries for everyone.

Going into the Green

Even if you’re not a genealogy, history, or architectural buff, cemeteries have plenty to offer. Significantly, they’re green. In addition to being a cemetery, many burial grounds house enough native tree species to also earn a designation as an arboretum. When visiting a nearby arboretum-cemetery combo, you have the chance to learn about the local ecosystem and discover hidden stories from the past.

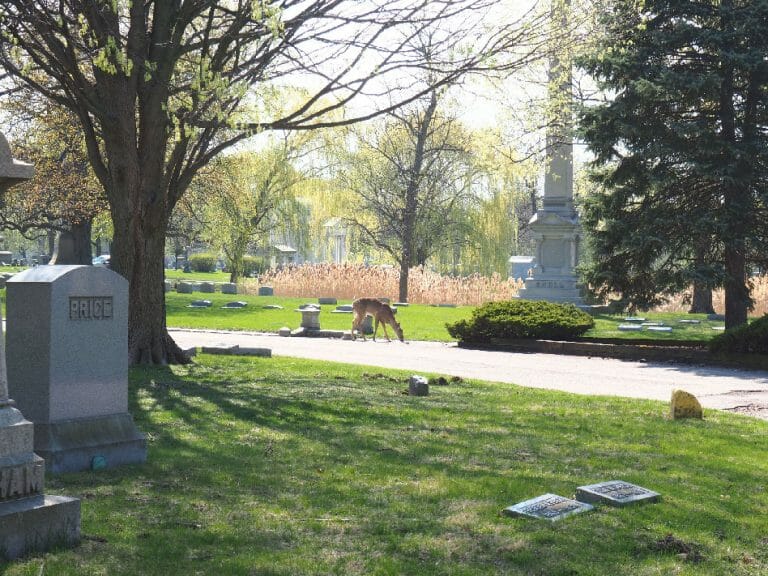

“In some cities, cemeteries are the only green space for residents and local wildlife have to enjoy,” DeRaddo says.

Artist and Business Coordinator at the Northwestern University Art History Department Mel Kaiser studies and creates art on the process of dealing with death. Additionally, she often organizes events for a Death Studies group at Northwestern. She’s spent time in cemeteries as research for her art. After that research, Keiser came to see cemeteries as a “place where people are using their bodies to gift future generations green space.”

On an unexpected summery day in Chicago this April, I decided to enjoy the warmth by visiting Rosehill Cemetery. It’s a massive 350-acre expanse of rolling grass, elaborate memorials, and reflective ponds. It was daunting to walk in, confronted with so much to see. I was surprised when a man in a truck rolled up next to me to say, “Walk about a half mile that way, there’s about 20 head of deer.”

He pointed to a vague area ahead of me to the left. Sure enough, I came across two shy deer poking their heads around a tree to evaluate me. They were the first deer I’ve seen in Chicago after over two years in the area. Surprisingly, life flourishes in places dedicated to the dead. Likewise, DeRaddo says she often runs into deer or rabbits on her outings to clean up tombstones.

Cemeteries’ Secret Culture

One special outcome of visiting a cemetery is getting to know the culture and personality of a place. Bright colors and music fill some places’ cemeteries, so communities may bond over losses. Others are quiet and calm, providing a setting for intimate reflection and grieving.

The best learning comes out of looking up the names you stumble upon in your wanderings. For instance, I never knew the story of the SS Eastland tipping over in the Chicago River until I visited Bohemian National Cemetery. The sculpture of a sinking ship wheel sparked my curiosity, and it led me to a new understanding of local history.

The stories are truly remarkable, even those belonging to small, trodden-over tombstones. Simple epitaphs, with just a name, birth date, death date, and relationship — “son” or “mother” — can say a lot.

“Even if we haven’t experienced the death of a mother, we can think about what it would mean to lose a mother,” Kesier says.

The stories are DeRaddo’s favorite part of cemetery wandering.

“I don’t believe that death is the period at the end of your story,” she says. “A person’s legacy, big or small, can live on through their headstone.”