According to the National Association for Gifted Children, six percent of students in the United States are enrolled in gifted and talented programs. However, I failed to find a statistic for the percentage of burnt-out, former gifted kids. This doesn’t mean they don’t exist. It’s simple physics: what goes up, must come down.

Define ‘Gifted’

‘Students, children, or youth who give evidence of high achievement capability in areas such as intellectual, creative, artistic, or leadership capacity, or in specific academic fields, and who need services and activities not ordinarily provided by the school in order to fully develop those capabilities.’

Elementary and Secondary Education Act

The long journey to burnout begins here, in the formal definition of ’gifted’. Students are expected to maintain an outstanding output level and are isolated from their peers to achieve their potential. Often, this forms a distinct but unsustainable identity. For a child to be gifted, they must show a higher aptitude than their peers. Therefore, the idea of a gifted student wouldn’t exist without comparison.

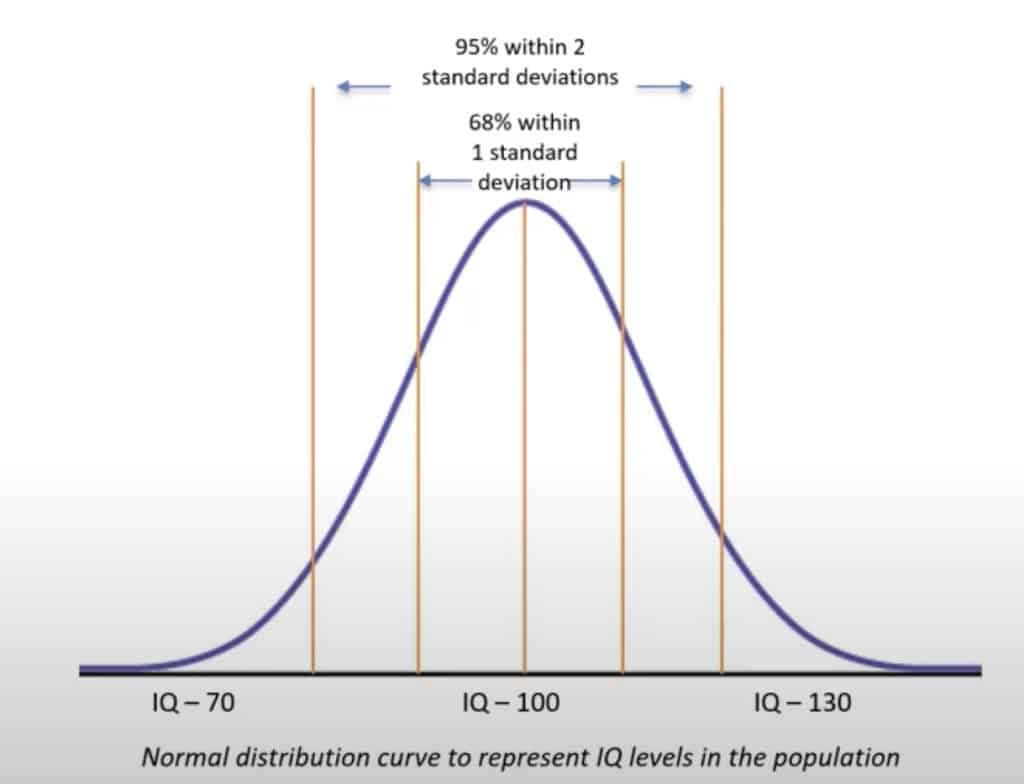

However, words are just one way to define a gifted student. IQ tests are also used to identify pupils who excel. As a rough guide, any individual who achieves 130+ is moderately to exceptionally gifted. Pupils who score this high are statistically ‘abnormal’ and therefore deviate from statistical norms. Yet, though a numerical method may seem more objective, most IQ tests are culturally biased.

Cultural Differences

In ‘Intelligence Testing and Cultural Diversity,’ Donna Ford highlights the lack of diversity in IQ examinations. Low performance on standardized testing and a lack of representation in ‘gifted’ programs are just two outcomes for racially and linguistically diverse students. Often, intelligence tests rely on general knowledge. Because this is grounded in the home and school environment, the information students can access may be vastly different.

‘Gifts and talents can only exist in a cultural context – a collection of references made up of expectations, behaviour, values and meanings shared by members of a community.’

Freeman, Joan. ’Giftedness in Different Cultures’. Mensa. (2020).

Freeman, in ‘Giftedness in Different Cultures,’ explores variations in education systems worldwide. Western ideology prioritizes individual achievement and unique thought in a select number of pupils. By contrast, Indian, Chinese, and Japanese views encourage hard work in all students to achieve success. Whereas most UK schools offer ‘gifted and talented’ programs to select children, in Japan, many students flock to Juku (“cram school”) in the evenings. Here, pupils participate in voluntary classes to aid test preparation and supplement academic work.

Gifted Kid Burn Out

Shock horror: not everyone is destined to become a genius. The dreaded burnout comes after prolonged emotional, mental, or physical exhaustion. Children who form an identity around being intelligent, or excelling in their field, are often exposed to high-pressure environments. Imagine a balloon: It falls to the floor if you don’t keep it in the air. The same happens with education. Without continued reassurance and validation, motivation decreases, and burnout occurs.

Perfectionism. A value instilled in almost every ’gifted’ child. With a natural aptitude for academics, this is often easy to uphold… at the start. As lessons become harder and workload builds up, high achieving students who previously didn’t have to learn study skills or time management habits begin to fall behind. An identity that once defined them is now a thing of the past.

‘It’s a lot easier to burn out as an academically gifted child because initially, you don’t struggle with the work. Eventually, you reach a point in your academic career where it’s no longer easy. You’re forced to learn how to study to upkeep your reputation of a high achiever. It’s a lot more stressful. Most children don’t have these expectations placed upon them to start with. That’s why gifted children burn out so much quicker.’

Riana Bahl, Kings College London, Second Year

King of The Castle

After some extensive research (a few Instagram polls), I concluded that being ‘gifted’ is often associated with natural talent. Yet, although a gifted student might have a lot of potentials, success will always require hard work. And the more potential, the more effort. What takes longer to build, a castle or a bungalow? A castle, right? Just because you’re told you can build a castle doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy. When everyone else has finished their bungalows and settled down to watch some Netflix, you’ll still be laying down the foundations.

At this point, you’re left with two options. Lower your expectations and settle for a less impressive but very comfortable bungalow. Two: keep going, and you’ll have a castle a few years down the line. The right choice? Whatever feels most achievable for you.

The aim of ‘gifted and talented’ schemes, clubs, and classes makes a lot of sense. Logically, children with higher aptitude need to be challenged… we’ve all watched Matilda. However, the semantics of the word ’gifted’ don’t sit right with me; the term separates children from their peers and teaches them that their success is defining. Although there may not be a solution to the problem, with more and more kids burning out, schools need to start prioritizing the mental health of high-achieving students.